BY SAAMAH ABDALLAH and LISA MÜLLER

Yesterday the ONS launched its most significant data set on subjective wellbeing since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in spring 2020. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic and associated restrictions have taken their toll on our wellbeing. For example, the percentage of people reporting low or medium life satisfaction in the second quarter of 2020 (April to June) was 17% higher than in the equivalent quarter in 2019. If anything, the fall in life satisfaction is perhaps smaller than one might have expected. However, anxiety rates do seem to have risen more sharply – with the ONS reporting the highest levels of anxiety in the UK in Q2 of 2020 since records began in 2011. So, if you are feeling a bit blue, you’re not alone.

At the Centre for Thriving Places, we’ve been using our Happiness Pulse to monitor data on subjective wellbeing since before the pandemic began. A wide range of people have used the Pulse, from individuals curious about their own wellbeing to organisations using it as an evaluation tool for wellbeing interventions. The new data from the ONS confirms what we’ve seen in our own analysis. For example, the decrease in mean life satisfaction of almost 0.2 (on a 0-10 scale) that the ONS reports between the spring and summer of 2019 and the spring and summer of 2020 almost exactly matches what we saw in the Happiness Pulse.

But the Happiness Pulse allows us to explore the impacts of the pandemic on other measures related to wellbeing, including people’s day-to-day behaviours and more detailed features of ongoing mental wellbeing. Furthermore, while the ONS figures report up to September 2020, we’ve run the numbers right up to 3 February to see what has changed as a result of the second lockdown.

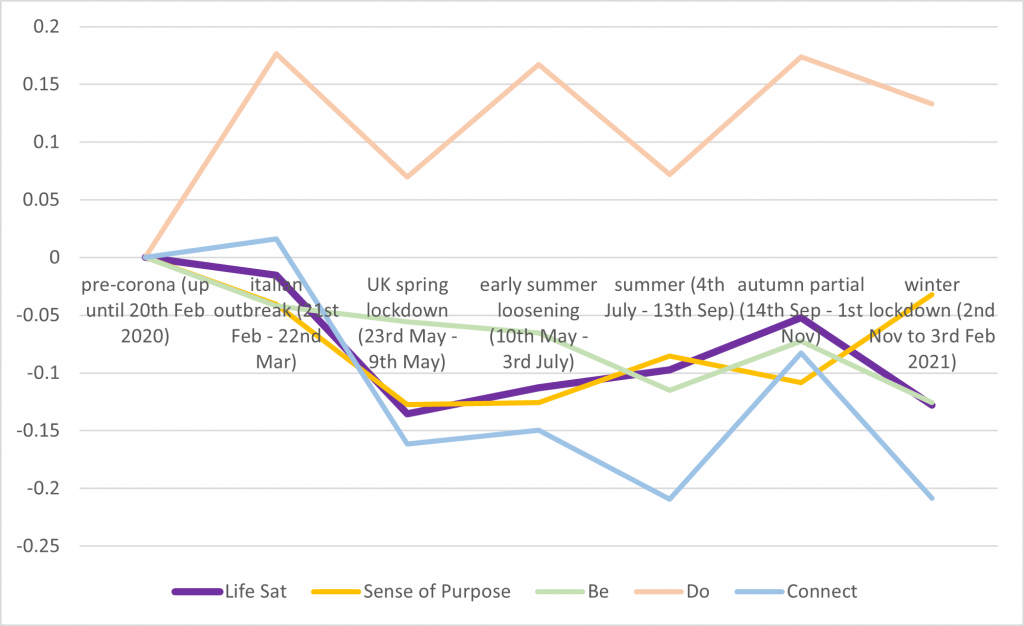

The graph shows the story for life satisfaction, sense of purpose, and the three main components of the Happiness Pulse – Be, Do and Connect.

The values plotted are standardised change coefficients compared to the period before Covid-19 hit Europe, based on an OLS regression including demographic control variables and dummy variables to adjust for the inclusion of several projects that have used the Pulse.

Unsurprisingly, the fall in the score for Connect is even bigger than that for life satisfaction. This domain includes questions about meeting socially, helping out and volunteering and feeling supported by those around you. For example, during the spring lockdown, 26% of regular Happiness Pulse respondents reported meeting friends, relatives or work colleagues socially less than monthly compared to 18% before the pandemic. This percentage remained at 22%, i.e. above the pre-Covid baseline, even during the summer of 2020 when restrictions were at their minimum.

More surprising is the consistently high scores seen in the Do domain, which includes questions on being active, learning and taking notice (three of the five evidence-based ways to wellbeing identified by the New Economics Foundation). For example, at the height of the lockdown in spring, 36% of respondents reported doing 30 minutes of sport or physical exercise every day or almost every day, compared to 22% pre-pandemic. Meanwhile, although scores for learning fell sharply during the spring lockdown, they quickly rose above pre-pandemic levels as restrictions relaxed over the summer. For example 59% of respondents reported spending time informally learning something new at least once a week between 10 May and 3 July, compared to 46% pre-pandemic and 38% during the spring lockdown. It seems that, at least in the case of the Happiness Pulse sample, people found ways to use the dramatic changes in lifestyle to the benefit of their wellbeing. This links to some of the findings of the UCL Covid Social Study published on the What Works Centre for Wellbeing blog last week.

The ONS data cannot yet tell us what has happened to wellbeing in the UK since the start of the second wave in autumn 2020. Our data tells us a few things. First, life satisfaction does seem to have fallen sharply again since the start of the second lockdown in November 2020 – it is now at a similar level to the spring lockdown. Connect has fallen to its lowest levels yet. However, people still seem to have maintained their new habits. One interesting story is the increase in people’s ability to take notice and appreciate the small things in life, with 29% strongly agreeing with this statement during the current winter lockdown, compared to 22% pre-pandemic.

One interesting story is the increase in people’s ability to take notice and appreciate the small things in life

One worrying trend is the decline in the score for the Be domain, which used the Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) to measure what should be a more stable and resilient aspect of wellbeing. Sure enough, while scores on this domain did not decline significantly during the first lockdown in spring, they are now significantly below pre-pandemic levels. Perhaps unsurprisingly, optimism is one of the clearest victims of the sustained pandemic situation, with the percentage reporting often feeling optimistic about the future decreasing from 49% pre-pandemic to 45% during the first lockdown and 41% during the current lockdown.

Our Happiness Pulse helps you measure, understand and improve wellbeing using a simple online survey – see how it could benefit you or your work.

Notes

The graph is based on data from 7,737 respondents who completed the online Happiness Pulse survey. Of these, 1,629 were invited to complete the survey as part of the evaluation of specific projects. These respondents tended to have lower wellbeing. To avoid their responses distorting the time trend, we included dummy variables for the three projects which allowed us to control for this effect whilst still using the data in the main analysis. However, for the data reported in the text based on single questions, only respondents who did not participate in these projects were used.

Of course, the official data collected by the ONS as part of the Annual Population Survey should be seen as the gold standard in terms of validity. The data from the Happiness Pulse cannot be seen as representative of the population as a whole, those who chose to complete the survey individually are likely to do so because of an interest in wellbeing. Nevertheless, we believe that our survey has one advantage over the regular Covid Social Study conducted by UCL, in that respondents do not select in because of a specific interest in Covid. As such, we avoid the risk of exaggerating the impact of the pandemic on wellbeing by using a sample that is likely to be more concerned about the pandemic than the general population.

Comments are closed.