There’s no denying it – self-denial is in our bones. Most of us sign up to it at some level – the endless diets, the dry Januaries, sacrifices made to prep for a marathon, even broadcasting how hard we work and how sleep-deprived that leaves us. Nobody wants to be seen as greedy, lazy or profligate. The uber-rich disgust us with their superyachts, mansions for their pets or toothpicks made of gold: many people challenge such excess by embracing simpler lives that enable them to live well on little.

Ideals of self-control, moderation and austerity have a long history. Moderation, or sophrôsyne, was one of five essential virtues in ancient Greece. Socrates took his moderation to extremes – he cheerfully trawled barefoot through the streets and marketplaces of Athens, in rags. Even the Epicureans, known for their devotion to achieving a life of pleasure, believed this could only be attained by understanding the true value of material goods and strictly controlling the desire for them.

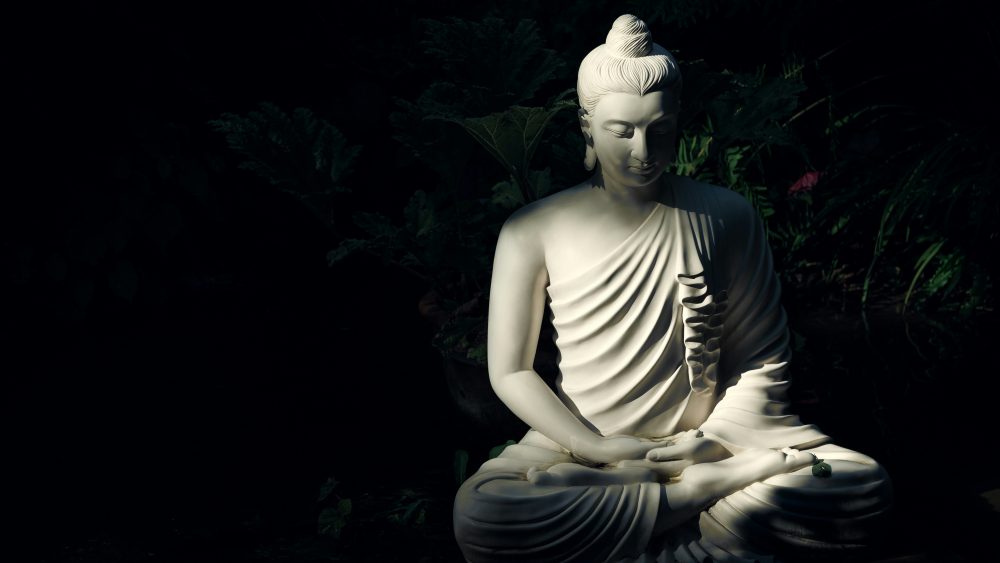

In other traditions, the ascetic life is revered as a mark of virtue, holiness, or spirituality – Christian monks have long taken a solemn vow of poverty, Buddha adopted a life of extreme self-denial to achieve enlightenment, Hindu Sanyasi renounce worldly desires to focus on spiritual pursuits, the Islamic Sufi tradition encourages abstinence from all that distracts from the worship of God.

The history of moderation or austerity gives us invaluable lessons in how to focus on what really matters and what we should sacrifice to achieve our life goals. Moreover, their insights are crucial in helping us develop the mental resilience required to keep on living well in the face of the misfortunes that life inevitably throws at us.

However, a perceptive article by Sarah Macmillan suggests the long-time love affair with personal self-denial and austerity makes it easier for politicians to justify ‘austerity’ on a national scale.

An admiration for austerity as a good in itself – a ‘moral’ way to live – may tempt people to buy into the myth that national austerity is ‘good for us’ and that government spending is in itself bad. The language of austerity politics tells it all. Good governments make cuts to ‘save for a rainy day’, don’t ‘run up the national debt’, ‘hold their nerve’ with their ‘financial discipline’. Bad governments ‘go on a spending spree’, ‘waste money’ on public services (there’s no magic money tree!), ‘bloat’ the public sector and raise the tax ‘burden’ on citizens to pay the bills. Accordingly, we are persuaded that coming together to make ‘sacrifices’ for the common good is the ‘moral’ choice – even when those sacrifices disproportionately impact on the most vulnerable in society.

Spending with wisdom is not a vice, but a virtue. Our governments can do the moral thing, not by locking our national budget away, but by spending to invest in wellbeing for all of the members of our society today, and for the wellbeing of future generations. Let’s explode the myth that the worthiness of personal moderation and self-denial can simply be writ large on a national stage and let us banish the moralising language of national austerity for good.

If we do this, we will be free to focus our public conversations on the important question of how we can #investin our common resources for the prosperity of all.

Imogen Smith – Happy City contributor

Photo by Mattia Faloretti on Unsplash

Comments are closed.