Insights on the natural environment, sustainability, and place-based wellbeing inequalities from the Thriving Places Index 2022

With the world’s leaders having gathered for another global summit on Climate Change (COP27), do you have to be a climate campaigner to care about the outcomes? For the many who are dealing with the hardships of everyday life amid an energy and cost of living crisis, it might be hard to find the motivation to care about something as seemingly ‘other’ as the global climate. But care we should.

One reason to care about protecting the quality of our natural environment is that it’s good for you. People who spend time in nature report better wellbeing. In a smartphone study of over one million responses from 20,000 participants in the UK, people reported feeling happier outdoors in green and natural spaces than in urban environments. People who live in polluted areas are less satisfied with their lives, in part because they spend less time outdoors and exercising. Engaging in pro-environmental behaviours like recycling is linked to better wellbeing, too.

It isn’t simply the case that people with higher wellbeing choose to spend time in green spaces – but that green spaces promote wellbeing. The evidence is strong because even randomly assigning people to spend time outside boosts how happy they feel. Recent research shows that being assigned to take a walk in nature rather than down an urban street promotes positive changes in the brain regions associated with stress reduction. These results can be partially explained by the mechanism of attention, because nature is constantly changing and attracting people’s attention in positive ways. Even simulations of nature can have a positive impact, though not as much as actually being in nature.

Evidence about the benefits of the natural environment for wellbeing is growing. The NHS is testing the effects of ‘green social prescribing’ to improve mental and physical health, which recommends patients attend nature-based activities like walking and community gardening. Yet recommendations to individuals can only go so far. There are persistent and substantive inequalities in the quality of local natural environments available to people, including access to green space and exposure to air pollution. Prescribing time outside may not work well for those without the time or ability to access quality outdoor spaces. Such issues are likely to be a focal point during COP27.

The Thriving Places Index (TPI) is a way to measure many of the vital ingredients for our wellbeing at a local level, including access to green space. It helps decision-makers prioritise and protect the availability of these ingredients (local good jobs, opportunities to learn, access to health and services, strong and cohesive communities and so on) but also keep track of how equitably the access to these ingredients are.

While the focus of this month’s COP27 may not be on local green spaces, or improving our wellbeing, it will direct our attention, in part, on tackling unfair and avoidable inequalities driven by climate change. Inequalities can arise directly, such as due to destruction of homes, and indirectly, including from global events that drive up energy, food and fuel prices. They can also arise from differences in people’s abilities to access their local environment, such as according to income, disability, time pressures, or culture and ethnicity. It is important to give a global stage to sustainable development given global inequalities in sustainability, but local action is important, too. The TPI can show us where action is most needed at local levels in the UK.

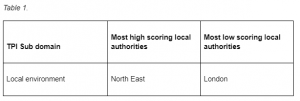

Regional results for the Local Environment sub-domain in the TPI help us look beyond the traditional North-South divides. The indicators for Local Environment include access to private and public outdoor spaces, air pollution, nitrogen dioxide concentrations, and transport-related noise. On the Local Environment TPI sub-domain, the North East has the best conditions, whereas London has the worst.

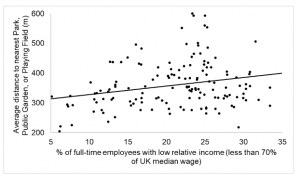

Importantly, it is also harder to access green space in areas where incomes are low (see Fig 1, which plots local authorities on these indicators).

Figure 1

While this is far from an answer to the global climate crisis that we all face, it’s an important factor for local governments to consider in their response to the challenges discussed at COP27 and beyond. Protecting our natural environment and tackling inequalities in access to it, is one lever of change that is firmly in their grasp – and one that will help the wellbeing of current and future generations of local communities.

By Laura Kudrna, Lailah Alidu, Iman Ghosh, Jessica Pykett, Holly Wilson, with input from Liz Zeidler

Comments are closed.