By Sam Wren-Lewis

The Centre for Thriving Places recently teamed up with the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) to look at the state of loneliness across the UK. In particular, the project looked at how people’s levels of loneliness have been impacted by the pandemic. You can read the ONS article outlining all the data analysis and key findings here.

This blog post looks specifically at what we found out about the local conditions associated with people’s levels of loneliness. With national and regional lockdowns and other forms of social distancing, it’s been a difficult time for everyone to feel connected. But have some places in the UK fared better than others? And if so, why?

Loneliness matters

Before looking at the national picture, it’s important to understand why loneliness matters. Everyone feels lonely from time to time, but chronic loneliness – feeling lonely ‘often or always’ – can have major negative impacts on people’s mental and physical health. We know from previous research that the health impact of chronic loneliness is equal to other public health priorities like obesity and smoking.

At the beginning of the pandemic (between 3 April and 3 May 2020), 5% of adults in the UK were chronically lonely – about 2.6 million people. Over the course of the pandemic (from October 2020 to February 2021), that proportion rose to 7.2% of adults, about 3.7 million people. That’s an additional million people becoming chronically lonely over the pandemic.

What makes people lonely?

The reality of feeling alone is not what many people think. Perhaps the most surprising finding is that young people feel much lonelier than older people. During the pandemic, nearly two thirds of students have reported a worsening in their mental health and wellbeing, with over 25% reporting to be chronically lonely, a significantly higher amount than the adult population (8%).

Other factors are more intuitive: people who are unemployed, single or living in a one person household are all more likely to report feeling lonely over the pandemic. People living in the countryside are much less likely to be lonely than those living in urban areas. This is presumably because of the stronger local connections that tend to exist in more rural communities.

‘The most important determinant of loneliness is simply a lack of social support’

But the most important determinant of loneliness is simply a lack of social support. According to one survey, around two thirds of adults in the UK have no one to talk to about their problems, such as their mental health, relationships or financial situation. Having no one to talk to made people ten times more likely to be lonely during lockdown – significantly more than any other factor (in comparison: being young made people 4 times more likely; being single made people 2 times more likely). Social isolation was the key driver of loneliness during the pandemic.

How can we prevent loneliness and social isolation?

It’s shocking that there are so many people in the UK who feel they have no one to talk to. But what can we do about it? In the analysis with the ONS we looked at the local conditions that prevent social isolation and loneliness, beyond individual factors such as age and unemployment.

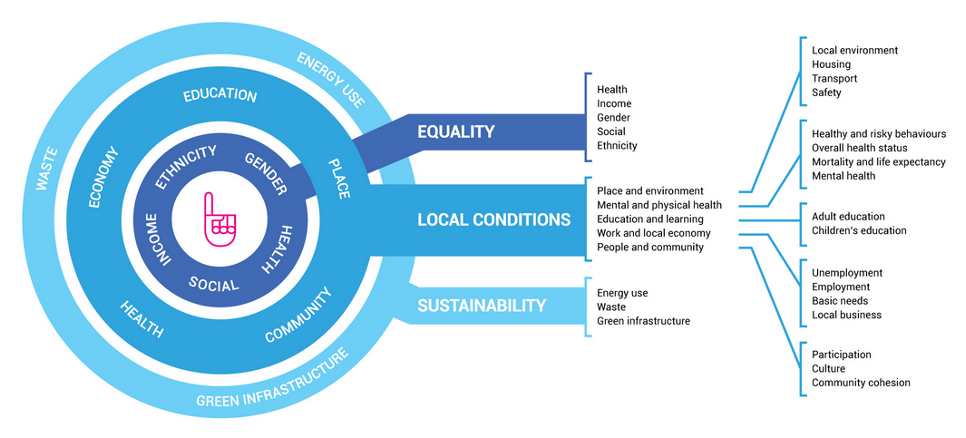

Using data from the Thriving Places Index (TPI), we looked at the specific local conditions connected with people’s level of loneliness. The TPI consists of multiple indicators of local conditions that make a difference to people’s wellbeing, from housing, transport and education to employment, cultural participation, and community cohesion.

Whilst two of these indicators stood out in particular in this analysis – areas with strong local businesses and adult education tended to have lower rates of loneliness (this was especially the case in London), what we know from the growing body of wellbeing research is that the drivers of wellbeing, and of loneliness, are often much more systemic than that. The pattern of local conditions, in their totality, are strongly associated with people’s level of loneliness. Instead of there being a few key local indicators, it’s the total sum of how places support (or undermine) our wellbeing that we should consider. To prevent social isolation and loneliness we need to think and act across the system – better access to housing, transport and green space, opportunities for employment and education, healthy lifestyles and healthcare, cultural and leisure facilities and to be part of an active and empowered community.

This may sound like a lot, and it is. But that’s not something we should shy away from. As well as being such a difficult time for so many people, the pandemic also has also provided us with a chance to rebuild society in a coherent way that makes things better for everyone. When it comes to loneliness and social isolation there are no silver bullets – what matters most is healthy communities. Building healthy communities requires a systemic view of the local conditions that have been shown to impact people’s wellbeing. The TPI is designed to support places to better measure, understand and improve those conditions in a really practical way. If we’re serious about tackling loneliness across the UK, we must focus on the capacity of us all to thrive, equitably and sustainably going forward.

Sam is a writer and data scientist with extensive experience in wellbeing research and measurement. He’s worked on numerous wellbeing policy projects with a range of local, national and international organisations and is CTP’s Wellbeing Measurement Advisor.

If you’re interested in learning more about how Centre for Thriving Places can support a place-based approach to growing wellbeing for all, please contact us at hello@centreforthrivingplaces.org

Picture – Elter Eric, Unsplash

Comments are closed.